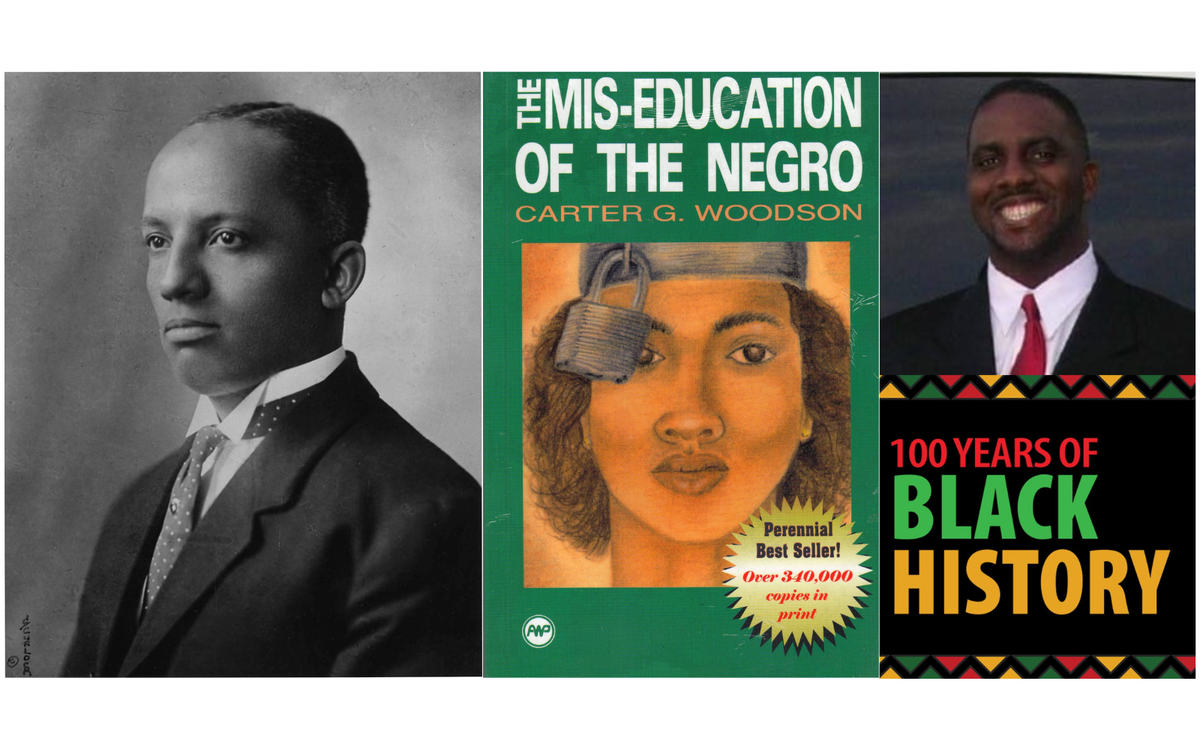

100 Years of Black History: How Carter G. Woodson Changed America’s Story

From a single week in 1926 to a national movement, Black history has reshaped education, culture, and democracy.

One hundred years ago, a scholar named Dr. Carter G. Woodson launched what would become one of the most enduring educational and cultural movements in American history: the formal study and public recognition of Black history.

In 1926, Woodson introduced Negro History Week, a response to an education system that largely ignored—or distorted—the contributions of people of African descent. His goal was not simply to celebrate but to also correct. Woodson believed that a nation could not fully understand itself while erasing the history of millions of its citizens.

A century later, that effort has evolved into Black History Month and beyond—shaping classrooms, scholarship, public policy, and cultural identity across the United States, including right here in Atlantic City.

A Radical Idea in Its Time

When Woodson, the son of formerly enslaved parents, earned a doctorate from Harvard University, he became only the second African American to do so. Yet he quickly realized that access to elite institutions did not guarantee historical truth. Textbooks of the early 20th century either omitted Black Americans entirely or reduced their story to slavery alone.

In response, Woodson founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now ASALH) and established Negro History Week to coincide with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. His message was clear: Black history was not separate from American history—it was essential to it.

Woodson warned that neglecting Black history produced what he famously called “mis-education,” a condition that harmed both Black Americans and the nation as a whole.

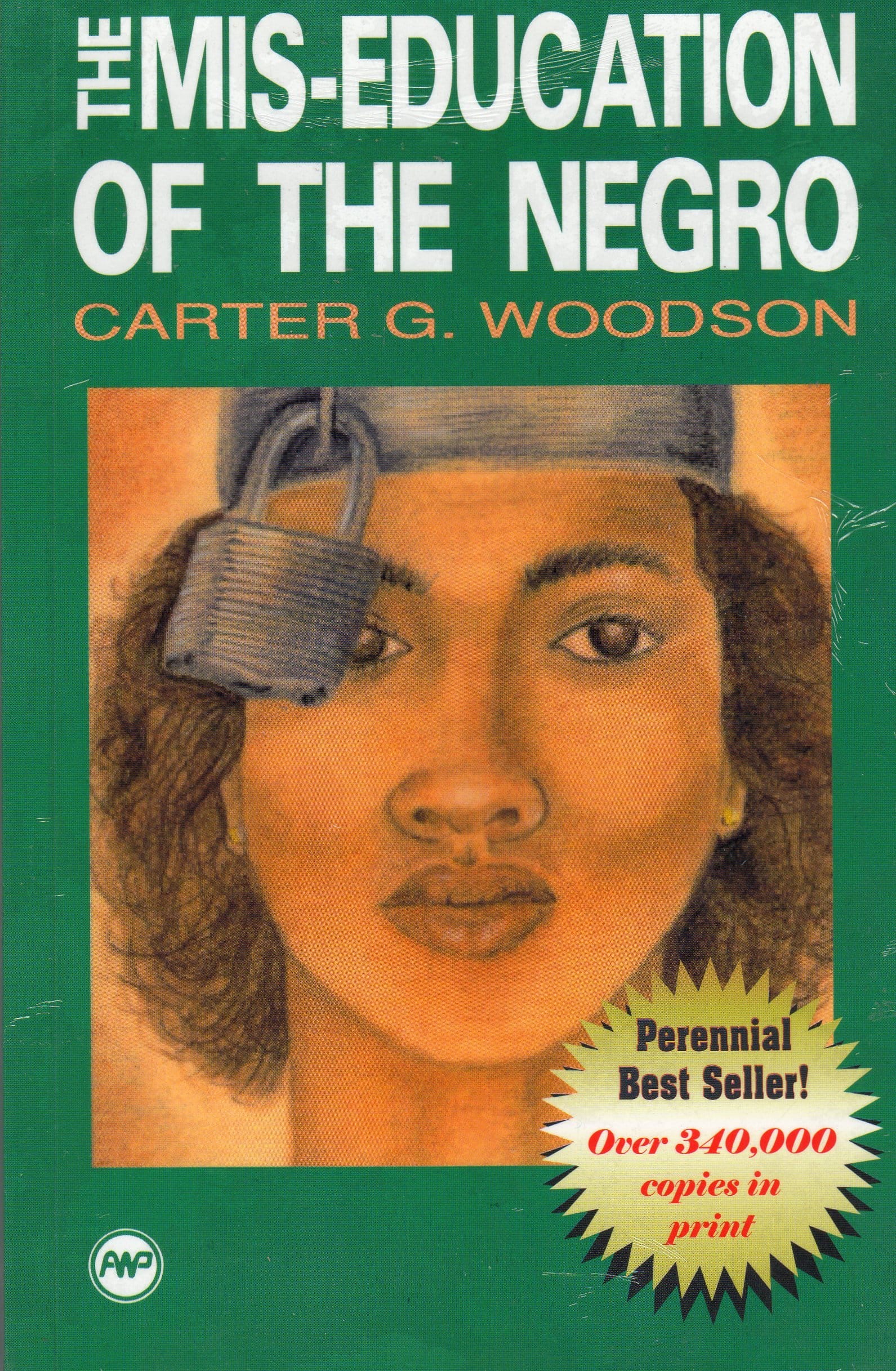

That critique reached its most powerful expression in his seminal 1933 work, The Mis-Education of the Negro.

In the book, Woodson argued that Black students were being systematically trained to admire European achievements while remaining ignorant of their own history, culture, and intellectual legacy.

“The same educational process which inspires and stimulates the oppressor,” Woodson wrote, “depresses and crushes at the same time the spark of genius in the Negro.”

Atlantic City: A Notable Exception

In The Mis-Education of the Negro, Woodson made a rare and telling observation: while most public school systems resisted the inclusion of Black history, Atlantic City stood out as one of the few exceptions where efforts were being made to integrate the study of the Negro into public school curricula.

In The Mis-Education of the Negro, Woodson made a rare and telling observation: while most public school systems resisted the inclusion of Black history, Atlantic City stood out as one of the few exceptions where efforts were being made to integrate the study of the Negro into public school curricula.

At a time when segregation and discrimination were the norm across much of the country, Atlantic City’s willingness to acknowledge Black history in education placed it ahead of many larger and more influential cities. That distinction underscores the city’s early role in recognizing the value of inclusive education—decades before such efforts became more widespread.

For today’s educators, students, and residents, that acknowledgment connects Atlantic City directly to the national roots of Black history education and affirms that local actions have long contributed to national progress.

From a Week to a Movement

By the 1960s and 1970s, amid the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, Woodson’s idea expanded. In 1976, during the U.S. Bicentennial, Negro History Week officially became Black History Month, gaining federal recognition and broader public adoption.

Since then, Black history has moved from the margins into mainstream scholarship. Universities offer African American Studies programs. Museums like the National Museum of African American History and Culture attract millions of visitors. Primary source materials once buried in archives are now digitized and widely accessible.

Yet the expansion has not been linear or uncontested. Debates over how race is taught in schools, whose stories are emphasized, and which histories are labeled “divisive” demonstrate that Woodson’s work remains unfinished.

Black History as Living History

One of Woodson’s most enduring lessons was that Black history is not static—it is ongoing. The last 100 years have documented seismic shifts: desegregation, voting rights legislation, the election of the nation’s first Black president, and the rise of Black leaders in business, science, arts, education, and local government.

Equally important are the stories of everyday people—teachers, clergy, laborers, activists, entrepreneurs, and students—whose lives shaped their communities in ways rarely captured by national headlines.

In Atlantic City and across South Jersey, Black history is visible in neighborhood churches, civic organizations, public schools, military service, small businesses, and cultural institutions. These local narratives reflect Woodson’s belief that history begins at home and belongs to the people who live it.

Why the 100-Year Mark Matters

Marking the 100th anniversary of Black history is not simply about looking backward. It is an opportunity to evaluate progress and responsibility.

Despite advances, disparities in wealth, health, education, and political power persist. Access to historical knowledge itself has become a point of contention, as educators and journalists navigate efforts to restrict how America’s past is discussed.

Woodson anticipated this tension. He argued that historical truth empowers communities to advocate for themselves—and that suppression of history weakens democracy.

Carrying the Legacy Forward

As Atlantic City Focus reflects on this centennial, we recognize Black history not as a once-a-year observance, but as a continuous civic obligation. Telling accurate, inclusive stories—past and present—is essential to community engagement, informed voting, and cultural understanding.

One hundred years after Dr. Carter G. Woodson lit the spark, the responsibility now belongs to educators, journalists, parents, and young people to keep the flame alive.

Black history is American history. And its next chapter is being written every day.

Sign Up for Atlantic City Focus Weekend Guide

Your Key to Winning the Weekend in AC and Beyond!

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Thanks for reading the whole story!

At Atlantic City Focus, we're committed to providing a platform where the diverse voices of our community can be heard, respected, and celebrated. As an independent online news platform, we rely on a unique mix of affordable advertising and the support of readers like you to continue delivering quality, community journalism that matters. Please support the businesses and organizations that support us by clicking on their ads. And by making a tax deductible donation today, you become a catalyst for change helping to amplify the authentic voices that might otherwise go unheard. And every contribution is greatly appreciated. Join us in making a difference—one uplifting story at a time!